April 22, 2005

40th Anniversary of Moore’s Law Heralded by Introduction of Dual Core Chips by Competitors AMD and Intel

Even as AMD launched the Opteron dual-core, we’re reminded of the words by Gordon Moore, co-founder of Intel Corporation and father of Moore’s Law, “No exponential lasts forever. But forever can be postponed.”

It was April 1965 when Moore made history by publishing an article in that month's issue of Electronics Magazine titled 'Cramming More Components Onto Integrated Circuits' which later became known as Moore's Law.

-

It has been 40 years since Gordon Moore first posited what would one day come to be known as Moore's Law. Today, we take many of the benefits of Moore's Law for granted. Yet if you look behind the curtains of the new breakthrough sciences, as well as many of the mundane, you will find semiconductors working. Much would not be possible without the relentless progress of the semiconductor industry doubling performance for the same price every two years or so, and that is what Moore's Law is all about.

In 1964, Electronics magazine asked Moore, then at Fairchild Semiconductor, to write about what trends he thought would be important in the semiconductor industry over the next 10 years for its 35th anniversary issue. ICs (integrated circuits) were relatively new. Many designers didn't see a use for them and worse, some still argued over whether transistors would replace tubes. A few even saw integrated circuits as a threat: if the system could be integrated into an IC, who would need system designers? The article, titled "Cramming more components into integrated circuits," was published by Electronics in its April 19, 1965, issue.

Moore's paper proved so long-lasting because it was more than just a prediction. The paper provided the basis for understanding how and why integrated circuits would transform the industry. Moore considered user benefits, technology trends, and the economics of manufacturing in his assessment. Thus he had described the basic business model for the semiconductor industry -- a business model that lasted through the end of the millennium.

From a user perspective, his major points in favor of ICs were that they had proven to be reliable, they lowered system costs, and they often improved performance. He concluded, "Thus a foundation has been constructed for integrated electronics to pervade all of electronics." From a manufacturing perspective, Moore's major points in favor of ICs were that integration levels could be systematically increased based on continuous improvements in largely existing manufacturing technology. He saw improvements in lithography as the key driver. From an economics perspective, Moore recognized the business import of these manufacturing trends and wrote, "Reduced cost is one of the big attractions of integrated electronics, and the cost advantage continues to increase as the technology evolves toward the production of larger and larger circuit functions on a single semiconductor substrate. For simple circuits, the cost per component is nearly inversely proportional to the number of components, the result of the equivalent package containing more components." The essential economic statement of Moore's Law is that the evolution of technology brings more components and thus greater functionality for the same cost. Computing power improves essentially for free, driving productivity in the economy, and thus fueling demand for more semiconductors. This is why the growth in transistor production has been so explosive. Lower cost of production has led to an amazing ability to not only produce transistors on a massive scale, but to consume them as well.

The economic value of Moore's Law is that it has been a powerful deflationary force in the world's macro-economy. Inflation is a measure of price changes without any qualitative change -- so if price per function is declining, it is deflationary. This effect has never been fully accounted for in government statistics. The decline in price per bit has been stunning.

In 1954, five years before the IC was invented, the average selling price of a transistor was $5.52. Fifty years later, in 2004, this had dropped to 191 nanodollars (a billionth of a dollar). If the semiconductor were fully adjusted for inflation, its size in 2004 would have been 6 million-trillion dollars. That is many orders of magnitude greater than Gross World Product. So it is hard to understate the long-term economic impact of the semiconductor industry.

So what makes Moore's Law work? There are three primary technical factors: reductions in feature size, increased yield, and increased packing density. The first two are largely driven by improvements in manufacturing and the latter largely by improvements in design methodology.

-

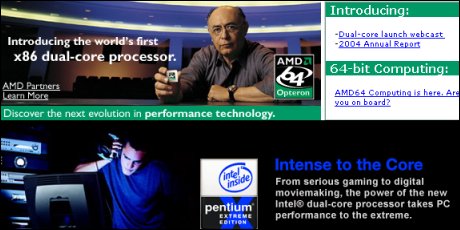

Intel beat AMD to the punch earlier in the week with the launch of its first dual-core processor, which was aimed at the high-end gamer and workstation market segments. In AMD's case, it has announced availability of the Dual-Core AMD Opteron 800 Series processor for four- and eight-way servers. In addition, it announced that the 200 Series for two-way servers will ship in May.

According to AMD, the new processors deliver up to a 90 per cent performance improvement for application servers over single-core AMD Opteron processors. For the desktop PC user segment, AMD announced the Athlon 64 X2 Dual-Core processor brand that the company stated will enable true multi-tasking capabilities for richer computing experiences.

"Just as AMD led the industry to pervasive 64-bit computing, AMD is now leading the industry to the performance and power benefits of multi-core processors," said Marty Seyer, corporate vice president and general manager, Microprocessor Business Unit, Computation Products Group, AMD, in a statement. "We have flawlessly executed manufacturing AMD64 processors, which is why today we are announcing the world's only broad dual-core client and server processor line-up, well ahead of our announced schedule. Because our non-disruptive dual-core architecture is designed to fit in today's existing infrastructure and provide leading-edge performance, enterprise customers can rapidly adopt AMD64 dual-core processors for servers and workstations today and for client platforms in June."

Several of AMD's OEM partners have also announced AMD dual-core server products. Sun Microsystems, HP and IBM have all announced dual-core platforms that will take advantage of the AMD64 technology.

According to AMD, dual-core processors are the next evolution of the company's AMD64 Direct Connect Architecture, and the processors were designed from the ground up to directly connect two cores on a single die, along with memory, I/O and dedicated caches. The company stated that the processors were also designed for easy and seamless migration. AMD's "non-disruptive upgrade path" allows users to upgrade single-core-based systems to dual-core-based systems because the dual-core processors were designed to work in the same power envelope and infrastructure as the single-core processors.

But Red Herring thinks it's advantage-AMD:

-

Advanced Micro Devices began selling the dual-core version of its Opteron chip on Thursday, giving AMD a slim advantage over Intel in a race to provide better processors for servers.

The single-core Opteron showed up in the marketplace two years ago, delivering a stunning blow to Intel. Opteron allowed business customers to use both the existing and more advanced software down the road. Intel’s server chips either didn’t have such capability or required expensive upgrades for companies that used servers with Intel processors.

More recently, Intel and AMD have competed hard on their dual-core products, which represent a departure from the old way of designing processors.

The dual-core chip has two processing units on the same piece of silicon. At a lower speed than a single-core processor, the dual-core chip can divvy-up the tasks and process more information at the same time while using less power.

In the past, chip engineers increased processor performance by increasing clock speed. To do so, they had to cram smaller and more transistors into a single-core chip, and such an approach ran into overheating problems.

Intel introduced a dual-core Pentium chip on Monday, but that processor isn’t designed for servers. So the dual-core version of Opteron gives AMD another advantage. Hewlett-Packard and IBM already plan to market servers and work stations featuring the new Opteron.

“Our customers say they want a product that retains the same power envelope, same wattage… but also offers the same performance. And the way to do that is through dual-core,” said Gina Longoria, Opteron product manager.

The news had been anticipated by Wall Street, and the stocks of both companies rose in recent trading as technology stocks rebounded from recent declines. Intel shares rose $0.42 to $23.08, while AMD shares climbed $0.20 to $14.85.

Intel’s high-end Pentium chip will power desktop computers favored by gamers and graphic artists. Intel plans to begin selling a computer processor for the masses, Pentium D, later this quarter.

AMD plans to start selling dual-core processors for desktop PCs in June and has given the PC processor a new brand name, Athlon 64 X2. Computers with Athlon 64 X2 will be good for handling multimedia tasks, such as photo editing.

Meanwhile, AMD will continue to sell single-core Athlon 64, believing that some consumers may not care to spend more money for souped-up computers.

And, AMD’s CEO, Hector Ruiz, is in firm agreement in his recent interview with EETimes:

-

Advanced Micro Devices this week rolled out its dual-core Opteron processor as part of its drive to usurp market share from Intel by developing a distinct product advantage. Hector Ruiz, AMD's CEO, discussed how Opteron will shape the Sunnyvale, Calif., chip maker's battle with Intel to win the hearts of minds of systems builders in an interview with CRN Editor In Chief Michael Vizard and Senior Editor Ed Moltzen.

CRN: When do you think dual-core Opteron systems will make an impact in the market?

RUIZ: I divide it into two parts. It will be rather dramatic in that it will force people to rethink their designs, but it will take some time to get things started. So the volume impact for us will probably be next year.

CRN: Given that, how much of an advantage do you think AMD now has over Intel, which is expected to roll out its dual-core offerings next year?

RUIZ: Intel is strong company and very capable. We just think this requires a lot more than a desire to do it. I don't know if you can retain their existing bus architecture and change it enough to get the level of performance and value that we have. If they change the architecture, that is not a trivial thing, so it will take them longer. And customers are already making an investment in the enterprise and are not just tip-toeing in the water.

CRN: Do you think software vendors are on board when it comes to pricing their applications based on a dual-core rather than a single-processor approach?

RUIZ: This is just starting, but the pressure is insurmountable in terms of going in this direction. Microsoft has taken the first step, and everybody will follow. Sun Solaris is the same way. We have major players signed up. At the dual-core level, I don't think this will be an issue. When we get to quad core, that could create a disruption.

CRN: When will that happen?

RUIZ: I'm perfectly confident that we will see engineering samples in 2007.

CRN: Over the last year, Intel has taken more of a platform approach to the market, which seems to be much different than AMD's approach. How much of a difference is there in the two companies' go-to-market strategies?

RUIZ: The good news is that you have a differentiated approach to the market, so channel partners now have a choice. How Intel and AMD are approaching the market is clearly different. We believe Intel's platform strategy is designed to continue their domination and control the market. But you can pick any three-year period [over] the last three years, and it shows that Intel generates all the profit and everybody else loses money. We believe that's crazy.

Systems makers want people to buy their brand because it has good value in it, not because it has Intel inside it. I think this is giving us an opportunity to go to customers that are becoming more interested in getting state-of-the-art CPUs from AMD and state-of-the-art motherboards from Foxconn to create a best-in-class system with their name on it. Our strategy is to continue to offer customers the option of not being marginalized. Any system builder that thinks warming up to the Intel platform brand is anything other than giving their soul away is nuts. They're naive.

CRN: Would you ever consider building your own chipsets?

RUIZ: I have not closed the door on that. If we do that, it would not be to create a platform. It would be to create a reliable source of supply rather than trying to marginalize the customer brand.

CRN: Most recently, AMD has experienced some profitability issues, especially as it relates to the flash memory business that the company is now preparing to spin off. When do you think AMD will return to profitability?

RUIZ: I didn't give any guidance to that. Profitability is important, but our No. 1 goal was to get the businesses positioned so they could develop a life of their own. The fact that the flash memory market went to hell is a temporary disruption. I'm not worried about how we're going to be profitable there. I was worried about microprocessors because in 2000 we had a phenomenal year, and we didn't make money then. It took a lot of changes and modifications over the years to get the microprocessor business to be consistently profitable over the last few quarters. We are on solid footing.

As the flash unit gets ready to spin off, it's pretty well-positioned. Last quarter, Intel had about $100 million more in flash sales than we did, but they lost $225 million on it. Our flash unit lost $39 million. We have better structure in the flash unit than any competitor. As the market recovers, we have a solidly positioned organization. I am pleased that we have been able to get the microprocessor business profitable and the flash business on solid footing.

CRN: Do you think Intel exacerbated the situation in the flash memory market to cut off a source of revenue for AMD's microprocessor business?

RUIZ: Funny how 999 people out of 1,000 actually think that.

CRN: Are you worried that Intel will try to use pricing on its single-core offerings as a tool to keep AMD at bay?

RUIZ: There are spots where they could choke us, but we think customers are warming up to the idea of having a viable, strong alternative. We're building the strength and momentum where pricing is not as effective as it once would have been.

CRN: How vital of a role does the channel play in your strategy?

RUIZ: The channel has always been a great partner for us when it comes to any product that we introduce. What is going to be different is that there are quite a few people in the channel playing a much bigger role in servers. Channel partners are starting to play a much bigger role in the enterprise. The help that we will get from the channel quickly will be pretty evident there. The people that we worked with that have been successful are people who really value creating a differentiated solution. We think single-core and dual-core Opterons strengthen that ability.

CRN: Are you going to spend a lot more money helping those partners market that differentiation?

RUIZ: We're going to have to change that, so this year we need to do something quite different. We obviously can't spend $2.1 billion on marketing. But we are going to work on that with partners. But what we spend will be an order of magnitude less than what our competitor spends.

The real question for consumers who only care about having the latest, fastest components in their box boils down to which is faster. On this front, at least according to reviewer Jason Cross at ExtremeTech.com – AMD wins handily:

-

A couple of weeks ago, we gave you a sneak peak at the performance of the new dual-core Pentium 4 processors from Intel. The chips, which are now shipping, are the first dual-core CPUs to hit the market. What's more, Intel started their push into multiple cores with desktop chips, rather than CPUs for servers.

AMD has been talking about dual-core chips for quite some time, and for awhile, was expected to be the first to the market with this technology. Accelerated plans from Intel changed all that, but the company is finally ready to ship dual-core chips. In contrast with Intel, AMD debuts their dual-core technology in their Opteron line, made for servers and workstations.

AMD's thinking is pretty simple: Server and workstation applications are more likely to be multithreaded than desktop PC apps. A dual-core processor would benefit those applications almost from day one. Intel is playing a different game, believing that the heavy multitasking environment in today's PC desktops will get a benefit. Both are right, in a sense, and both are playing to their relative strengths.

We recently got our hands on a dual-core Opteron test kit from AMD, and decided to pit it against the Pentium 4 840 Extreme Edition we previewed recently. These are not chips aimed at exactly the same markets, but the Opteron is so architecturally similar to an Athlon 64 in that it provides a reasonable facsimile of Athlon 64 desktop performance. There are differences, of course—Athlon 64 CPUs don't have as many hypertransport links for multi-CPU systems, typically ship at faster clock speeds, and don't use registered RAM—but the core architecture is nearly identical. Rather than test it as a pure server platform, we used a uniprocessor system and a desktop graphics card to see how a dual-core desktop Athlon 64 might perform.

The dual-core battle is far from over, of course. Intel is shipping dual-core desktop CPUs now, but the quantities aren't real high. The real battle will come later this year, as AMD releases Athlon 64 CPUs for desktops that feature two cores, and Intel's dual-core shipments ramp up. For now, let's take a look at how the two competing technologies stack up.

This is primarily a performance preview, but before we get into the numbers, we should take a quick look at the platform itself.

The test hardware we received from AMD consisted of two Opteron 875 CPUs, which are expected to sell for about $2,649 in lots of 1,000. That's AMD's most expensive chip—a dual core Opteron made for systems with up to eight CPUs together. Opteron dual-core chips will also ship in the 200 series, made for workstations and servers with only two CPUs. The model 275, suitable for two-socket systems, is priced at $1,299. The model 175, targeted at single socket servers and workstations, goes for $999. All are socket 940 processors requiring registered, buffered DDR memory.

The Opteron x75 ships at a clock speed of 2.2GHz. This is a significant reduction from the fastest single-core Opteron, model x52, which runs at 2.6GHz. Even with the transition to a 90nm manufacturing process, both Intel and AMD have to make significant reductions in clock speed to keep these dual-core chips from running too hot and eating up too much power. This allowed AMD to keep the thermal envelope at around 95W, which is better suited for server environments.

There are significant architectural differences between AMD and Intel's dual-core chips. Looking at the following two block diagrams, you can see that the primary difference is how each core interfaces with the rest of the system. Each of the two CPU cores on the Model 840 shares a front side bus to the memory controller hub (MCH) of the 945/955X chipset. AMD's dual core architecture also uses a single memory controller, which is on-die. Memory arbitration in AMD's case is handled through a crossbar switch that also has independent access to the HyperTransport links. In other words, each of Intel's cores must go "off chip" to talk to each other, while AMD's cores have a more direct line of communication.

AMD's dual-core products include the improvements made with the new "E4" stepping single-core Athlon 64 and Opteron CPUs. That is, they are made on a 90nm SOI (Silicon on Insulator) manufacturing process, have added support for SSE3, and a tweaked memory controller. It's a large chip, about 199mm2 and 233 million transistors, which makes it roughly equivalent in size to the Pentium 4 840 Extreme Edition. The thermal rating is 95 watts, considerably lower than the Pentium 4 840 EE's maximum thermal rating of 125 or 130 watts (we've heard both numbers out of Intel).

... later on, Cross gets to the point ...

-

There's really no other way to say it—this is a huge win for AMD. We expected major improvement in multi-threaded applications and multi-tasking tests, but at only 2.2GHz we weren't sure it would actually perform better than Intel's dual-core Pentium Extreme Edition 840. There are a couple of tests—usually single-threaded tests—where the Opteron 875 doesn't keep pace, but in the vast majority of benchmarks, AMD comes out ahead.

My own verdict? I’d personally rather have Dell launching my processor (Pentium 4 Extreme Edition) on its workstations, servers and (eventually all of) its PCs, than IBM’s Opteron commitment for the LS20 blade… although Lenovo will be nobody to sneeze at, for Intel either…

The battle for the future of the microprocessor has only just begun.

- Arik

Posted by Arik Johnson at April 22, 2005 12:06 PM "Competitive Intelligence applies the lessons of competition and principles of intelligence to the need for every business to gain awareness and predictability of market risk and opportunity. By doing so, CI has the power to transform an enterprise from also-ran into a real winner, with agility enough to create and maintain sustainable competitive advantage."

"Competitive Intelligence applies the lessons of competition and principles of intelligence to the need for every business to gain awareness and predictability of market risk and opportunity. By doing so, CI has the power to transform an enterprise from also-ran into a real winner, with agility enough to create and maintain sustainable competitive advantage."